Syria’s New Leader at the UN: A Nation’s Fragile Rebirth

In a historic moment for Syria, Ahmed al-Sharaa will address the United Nations General Assembly on Wednesday, marking the first appearance of a Syrian president at such high-level UN meetings since 1967. This watershed moment comes after al-Sharaa, once affiliated with extremist groups, led a successful revolution against Bashar Assad’s regime. Now dressed in Western-style suits rather than military fatigues, he seeks to present Syria’s vision for stability, reconstruction, and reconciliation on the global stage. As Natasha Hall from the Center for Strategic and International Studies notes, “This is a very big deal.” Al-Sharaa aims to emphasize that “this is a new day for Syria” after overthrowing what he calls “the brutal dictatorship of the Assad regime,” while advocating for international recognition and the lifting of UN sanctions to help his country move forward.

Syria’s path to recovery faces enormous challenges. The country requires between $250 and $400 billion for reconstruction after 13 years of devastating civil war. According to UN statistics, a staggering 75% of Syria’s population—approximately 16.7 million people—urgently need humanitarian assistance. Despite these obstacles, al-Sharaa has been on a diplomatic charm offensive, hosting European and Western diplomats in hopes of ending Syria’s international isolation. His efforts received an unexpected boost when he met with President Donald Trump in Saudi Arabia last May, where Trump called him a “young, attractive, tough guy” and announced plans to lift sanctions imposed during the Assad era. Al-Sharaa’s UN appearance represents an opportunity to secure crucial reconstruction aid and potentially even negotiate security arrangements with neighboring countries, including Israel.

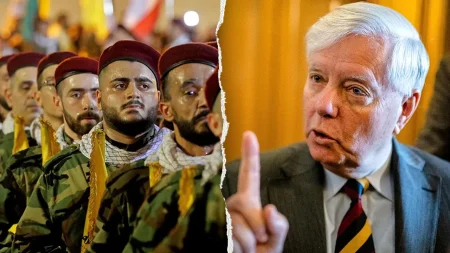

Since taking control of Damascus, al-Sharaa has made promising public commitments: establishing an inclusive government representing all religious and ethnic factions, upholding women’s rights, and protecting minorities. He’s taken concrete steps against terrorism, with Syrian security forces recently intercepting a weapons shipment destined for Hezbollah in Lebanon—formerly a key Assad ally. This action signals a potential break from Syria’s previous alignment with Iran’s “Axis of Resistance.” However, experts like former U.S. Ambassador to Syria Robert Ford remain cautious: “Al-Sharaa is not a democrat. He ruled Idlib without power-sharing.” While acknowledging that political freedom to speak and protest in Syria currently exceeds that in many regional neighbors like Egypt and some Gulf states, Ford emphasizes that the crucial question is whether individual political and civil liberties will be respected over time.

Ambassador Barbara Leaf, who became the highest-ranking U.S. official to meet with Syrian leadership since 2011 when she visited Damascus last December, offers insight into al-Sharaa’s approach. She found him “well-prepared” and “thoughtful” during their discussions, noting that he repeatedly emphasized that Syria would no longer serve as a staging ground for threats against its neighbors, including Israel. “I came to the sense that he was already making a shift from being a military commander to being a politician, to being a political leader,” Ambassador Leaf observed. However, she acknowledges the lingering uncertainty about his true intentions: “Does he want to formulate a kind of Islamist governance, conservative governance and social order that, frankly, Syria has not seen? And would he be willing to use force to get there? That’s an unknown.”

Concerns persist about the composition of Syria’s transitional government, with many key roles filled by al-Sharaa’s close associates and others affiliated with his former group, HTS. Caroline Rose, director of The New Lines Institute who traveled to Syria earlier this year, describes a “careful balancing act” within the government between liberal opposition voices, former regime bureaucrats, and more Islamist proponents. This complex dynamic has led to governmental paralysis during critical situations, including failures to control radical fighters during violent outbreaks in Latakia and Suwayda. Some policies, such as requiring full-body swimwear at Syrian pools and beaches, appear designed to appease more conservative elements of al-Sharaa’s support network, raising questions about the direction of social policies under the new leadership.

Syria’s transition remains precarious amid alarming sectarian violence. The country has experienced its worst bloodshed since Assad’s overthrow, with approximately 1,400 people—mostly civilians from minority Alawite and Druze communities—massacred in retaliatory violence. Clashes between various ethnic groups and government forces have resulted in hundreds of deaths, even drawing Israeli military intervention to protect Syria’s Druze minority. The country’s dwindling Christian community has also suffered, including a suspected Islamic State suicide bombing at a Greek Orthodox church that killed 22 worshipers. Additionally, the new government faces the challenge of incorporating Kurdish forces from Northeast Syria, who have been crucial to the U.S.-led counter-ISIS campaign. As al-Sharaa takes the UN podium, he carries the weight of a nation’s hopes for peace and stability, but also the burden of proving that his transformation from militant leader to statesman is genuine and capable of healing Syria’s deep wounds.