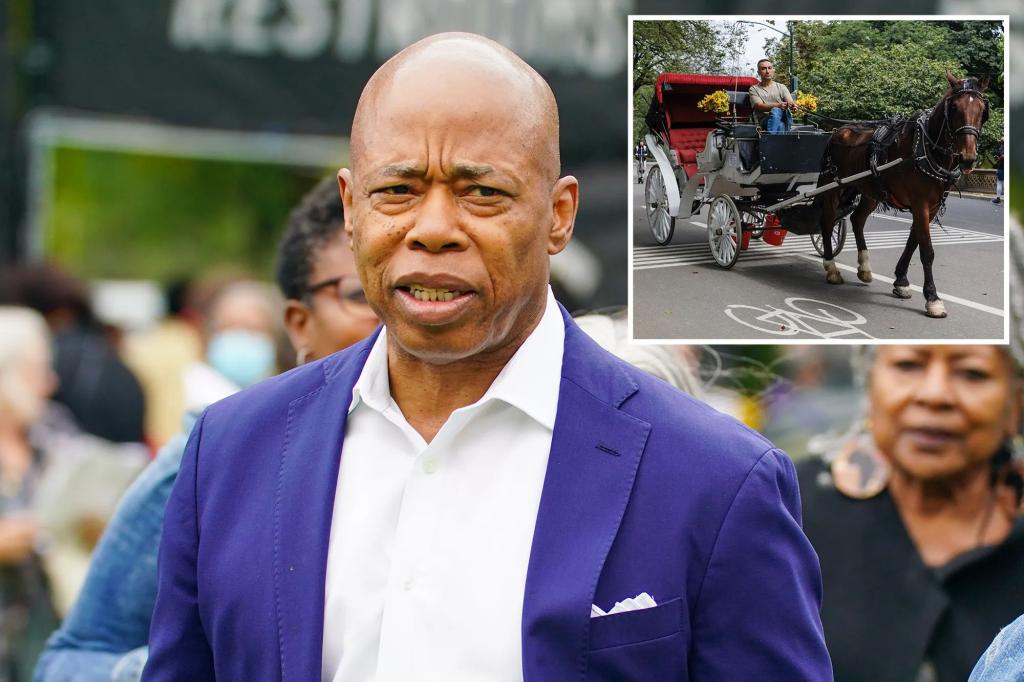

Central Park’s Horse Carriage Tradition Faces Imminent Ban Under Mayor Adams’ Leadership

Mayor Eric Adams is set to take decisive action against Central Park’s iconic horse-drawn carriages, signaling the potential end of a storied New York City tradition by late 2026. In an exclusive reveal, Adams plans to sign an executive order on Wednesday that begins a formal crackdown on the horse carriage industry, describing them as relics of old New York that “no longer work for our city.” This shift comes after a troubling summer where three separate incidents saw carriage horses running loose through the park, raising serious public safety concerns. The mayor’s position represents a significant turning point for an attraction that has long been synonymous with Central Park’s charm but has increasingly faced scrutiny over animal welfare issues. “While horse-drawn carriages have long been an iconic fixture of Central Park,” Adams acknowledged, “they are increasingly incompatible with the conditions of a modern, heavily-used urban green space.” His executive order, titled “preparing for the cessation of horse-drawn carriages in New York City,” aims to prepare the ground for a complete phase-out of the industry.

The immediate impact of the executive order will be a heightened enforcement of existing regulations through a coordinated effort between multiple city agencies, including the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection, Parks Department, health department, and the NYPD. Police will be directed to crack down on carriages illegally soliciting fares or operating in traffic and bicycle lanes—though the latter restriction presents practical challenges given Central Park’s recent redesigns that make such areas nearly impossible for carriages to avoid. The Department of Transportation has been tasked with studying current passenger boarding locations and identifying alternative spots in “less-frequented areas of Central Park,” effectively beginning to marginalize the industry’s operations. These measures represent an interim step while the mayor pushes the City Council to advance Ryder’s Law—legislation named after a horse who collapsed and died in service—which has been stalled in the health committee since last summer. “By voicing an opinion, we’re hoping it will give [the legislation] a push,” explained a City Hall representative, with the mayor adding, “We need the Council to do their job, step up, and work with us on comprehensive reform.”

The mayor’s decision draws directly from a series of concerning incidents that have highlighted both animal welfare and public safety issues. He specifically cited the deaths of horses Ryder and Lady as “troubling incidents” that demanded action. The executive order further addresses animal welfare concerns including exposure to traffic fumes, noise, hard pavement, and extreme heat—conditions inherent to urban carriage operations. This policy shift also follows the Central Park Conservancy’s recent stance against horse-drawn carriages, citing “public health and safety” concerns. The nonprofit, which maintains the park, had maintained neutrality on the issue for years before this significant position change just last month, adding institutional weight to the growing movement against the carriages.

Looking toward the future, the administration isn’t simply planning to eliminate jobs—the executive order calls on city agencies to identify “new employment opportunities” for those currently working in the carriage industry, with particular focus on keeping them within the tourism sector. City Hall has also outlined plans for a voluntary license return process for drivers, easing the transition away from the industry. In an attempt to preserve some elements of the tradition while addressing modern concerns, the mayor’s office expressed openness to exploring alternative tourist experiences, such as an electric carriage program that would allow “New Yorkers and visitors to continue to enjoy the majesty of Central Park.” Another possibility mentioned was the establishment of a horse stable within the park itself, potentially creating a more controlled environment for any remaining equine activities.

Adams has framed this significant policy shift not as an attack on tradition, but as an evolution of it. “This is not about eliminating this tradition—it’s about honoring our traditions in a way that aligns with who we are today,” the mayor explained, seeking to connect the decision to broader New York values. “New Yorkers care deeply about animals, about fairness, and about doing what’s right.” This framing attempts to position the phasing out of horse carriages as a progressive step forward rather than simply the end of a beloved custom, acknowledging the emotional attachment many have to these symbols of old New York while asserting that contemporary ethical standards require change. The approach reveals the delicate balancing act the administration is attempting: respecting the city’s heritage while adapting to changing social values and urban realities.

While the executive order represents a significant step, a complete ban still requires City Council approval, highlighting the complex governance process that surrounds such a culturally and economically significant decision. The timing of this push—coming after multiple high-profile incidents involving carriage horses and with the backing of the Central Park Conservancy—suggests the administration sees a window of opportunity to resolve an issue that has divided New Yorkers for decades. By setting a target date of late 2026 for the complete phase-out, the city is providing a transition period while sending a clear message that this traditional industry’s days are numbered in modern New York. As this story develops, it will likely continue to generate passionate debate between those who see the carriages as an essential piece of New York’s charm and those who believe the practice has become outdated and inhumane in today’s urban environment.