The intricate relationship between emotions and our physical sensations, a phenomenon known as embodied emotions, has been a subject of fascination for scientists and philosophers alike. A recent study delves into the historical roots of these associations, examining how people living in Mesopotamia thousands of years ago linked their emotions to specific body parts. By comparing these ancient perceptions with modern understandings of embodied emotions, the research reveals both surprising continuities and intriguing divergences in the way humans perceive and express their feelings. The findings highlight the complex interplay between culture, language, and the very fabric of our emotional experience.

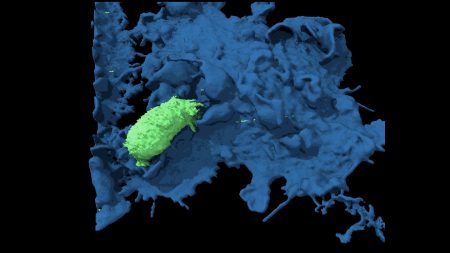

The study, published in iScience, focuses on the Neo-Assyrian Empire, a powerful civilization that flourished between 934 and 612 BCE in a region encompassing parts of modern-day Egypt, Iraq, and Türkiye. Researchers meticulously analyzed texts inscribed on clay tablets and other artifacts, cataloging the words used to describe both body parts and emotions. They then compared these ancient associations to modern-day mappings of embodied emotions, utilizing visual representations to highlight the similarities and differences in how people, separated by millennia, connected their inner feelings to their physical selves.

One of the most striking findings is the enduring link between the heart and positive emotions. Just as we might say our hearts “swell” with joy or pride, the ancient Mesopotamians also frequently associated the heart with feelings of love and happiness. This continuity suggests a deep-seated connection, perhaps rooted in the heart’s vital role in sustaining life, that transcends time and cultural boundaries. Similarly, the stomach, often associated with feelings of unease and anxiety in modern contexts, was linked to sadness and distress by the Neo-Assyrians, indicating another enduring association between a specific organ and a particular emotional spectrum.

However, the study also reveals fascinating divergences in how emotions were embodied in the past. A striking example is the association of anger with the legs and feet in ancient Mesopotamia, a stark contrast to modern perceptions that often locate anger in the upper body, particularly the chest and head. This difference highlights the influence of cultural and linguistic factors in shaping our emotional landscape. Another intriguing divergence is the ancient association of positive emotions, especially happiness, with the liver. This connection, largely absent in modern discourse, likely stemmed from the liver’s prominent size and its perceived importance in ancient medical and spiritual beliefs, where it was sometimes considered the seat of the soul.

The research offers a unique window into the evolution of our emotional lexicon and sheds light on the fluid nature of embodied emotions. While some associations, like the heart-happiness link, appear to be deeply ingrained and persistent across time, others, like the liver-happiness connection, have faded from common usage. This fluidity underscores the importance of considering cultural and historical contexts when interpreting emotional expressions. The study also raises questions about how these associations are transmitted and transformed across generations, through shared stories, religious beliefs, and cultural practices.

By examining the embodied emotions of a civilization separated from our own by thousands of years, the study allows us to gain a fresh perspective on our own emotional experiences. It challenges the assumption that our current ways of linking emotions to body parts are universally natural or self-evident. Instead, it suggests that these associations are, at least in part, shaped by the language and culture in which we are immersed. This realization opens up exciting possibilities for exploring the dynamic relationship between language, culture, and the very essence of what it means to feel. It encourages us to question the seemingly obvious and to appreciate the rich tapestry of human experience across time and cultures.

The research on embodied emotions in ancient Mesopotamia offers valuable insights into the historical roots of our emotional language. By comparing ancient and modern associations, the study reveals both enduring connections and intriguing divergences in how emotions are linked to specific body parts. This cross-cultural perspective challenges our assumptions about the universality of emotional experience and highlights the significant role of language and culture in shaping how we perceive and express our feelings. The findings pave the way for further exploration of the dynamic interplay between body, mind, and culture across diverse historical and geographical contexts, enriching our understanding of the complex human experience of emotion.