Deportation Controversy: The Case of Orville Etoria

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has launched a scathing critique of The New York Times over its coverage of Orville Etoria, a Jamaican national who was deported to Eswatini in July 2023 under the Trump administration. At the heart of this controversy lies a fundamental disagreement about how to frame Etoria’s story. The Times published an article with the headline, “The Man Who’d Served His Time In U.S. Is Deported to an African Prison,” focusing on Etoria’s rehabilitation during his incarceration and the unusual circumstances of his deportation to a country where he isn’t a citizen. DHS, however, responded furiously on social media, calling the article “disgraceful and disgusting” and accusing the newspaper of defending a convicted murderer at the expense of American citizens. This case highlights the ongoing tensions between journalistic approaches to immigration stories and the hardline stance of certain government agencies on deportation policies.

Etoria’s history in the United States is complex and spans nearly three decades. In 1996, he was convicted of murder after shooting and killing a man in Brooklyn, receiving a sentence of 25 years to life along with a deportation order issued in 2009. According to DHS statements, his criminal record also included armed robbery, weapon possession, and forcible theft. During his incarceration at Sing Sing Correctional Facility in New York, Etoria pursued education through the Hudson Link program at Mercy College, earning a bachelor’s degree in 2018 and later working toward a master’s in divinity. Following his release in 2021, the Biden administration permitted him to remain in the United States under ICE supervision, despite the existing deportation order. This period of relative stability ended with the change in administration, culminating in his deportation to Eswatini, a small southern African nation where he holds no citizenship.

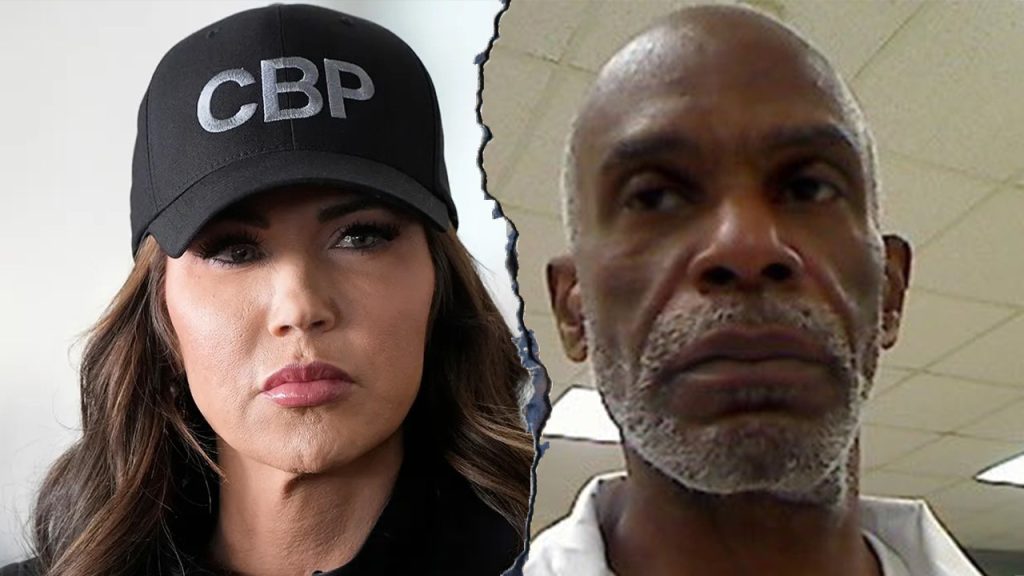

The deportation was part of a broader operation announced by DHS in July, which involved five individuals from various countries including Vietnam, Laos, Cuba, Yemen, and Jamaica. DHS spokesperson Tricia McLaughlin characterized these deportees as “individuals so uniquely barbaric that their home countries refused to take them back” and as “depraved monsters” who had been “terrorizing American communities.” The agency emphasized that these deportations represented a fulfillment of the administration’s commitment to removing criminal non-citizens from American soil. However, this characterization has been contested, particularly in Etoria’s case, where his post-incarceration life seemed to demonstrate significant rehabilitation. The decision to send him to Eswatini rather than Jamaica has raised questions about deportation practices, with DHS claiming Jamaica refused to accept him—an assertion that Jamaican officials have subsequently disputed.

The media framing of Etoria’s story exemplifies the polarized discourse surrounding immigration and criminal justice in America. The New York Times’ approach emphasized Etoria’s rehabilitation journey and the unusual circumstances of his deportation to a country with which he had no connection. Their narrative focused on questions about whether the punishment—serving a lengthy prison sentence followed by deportation to a third country—fits the original crime, especially given evidence of rehabilitation. DHS, conversely, centered its response on Etoria’s original crime, insisting that his murder conviction should be the primary lens through which his case is viewed. Their emphatic statement that Etoria is “a convicted MURDERER” (capitalization in the original) reflects a policy position that past violent crimes should permanently define an individual’s status and treatment, regardless of subsequent behavior or rehabilitation.

This case touches on several interconnected policy debates, including the purpose of incarceration, the possibility of rehabilitation, and the role of deportation in the American justice system. For those who view prisons primarily as institutions of punishment and deterrence, Etoria’s deportation represents appropriate consequences for a serious crime committed on American soil. For those who believe in rehabilitation and second chances, his educational achievements and apparent transformation during incarceration suggest that continued deportation efforts after serving his sentence constitutes a form of double punishment. The fact that he was sent to a country where he isn’t a citizen—rather than to Jamaica, his country of origin—further complicates the ethical considerations. This aspect of the case raises questions about international agreements, diplomatic negotiations between countries regarding deportees, and the rights of individuals caught between nations unwilling to accept them.

The confrontation between DHS and The New York Times over Etoria’s story reflects broader tensions in American society about immigration, crime, and media responsibility. DHS accused the newspaper of “peddling another disgusting sob story for a criminal illegal alien” and characterized their reporting as “actively defending convicted murderers over American citizens.” This language frames the issue not just as a matter of law enforcement but as a moral choice between protecting citizens and sympathizing with non-citizens who have committed crimes. The Times’ coverage, by contextualizing Etoria’s crime within his broader life story, including his efforts at redemption, presents a more nuanced view that questions whether justice is truly served by deporting someone to a country where they have no connections after they have already served their prison sentence. As Etoria remains in Africa alongside four other deportees, his case continues to serve as a flashpoint in ongoing debates about justice, rehabilitation, and the human consequences of immigration policy.