The Fight for Life: Utah Prisoner’s Execution Halted Due to Dementia

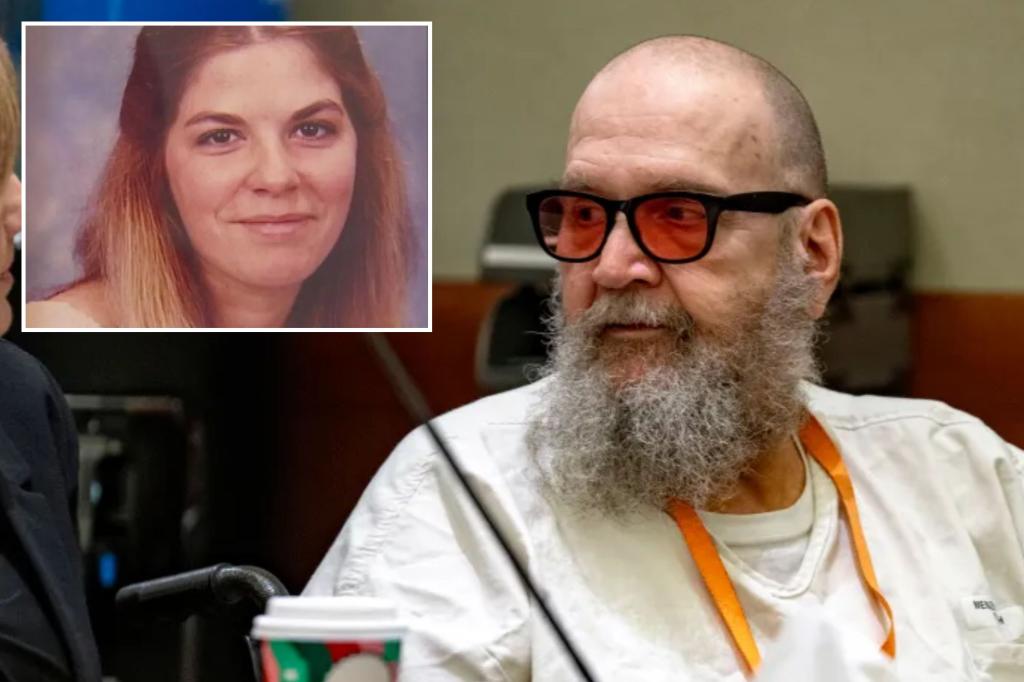

In a dramatic turn of events, the Utah Supreme Court has halted the execution of 67-year-old Ralph Leroy Menzies, who was scheduled to die by firing squad on September 5, 2024. This last-minute intervention came after his attorneys argued that Menzies, who has spent 37 years on death row for the 1986 murder of Maurine Hunsaker, a mother of three, now suffers from severe dementia. The court ruled that a lower court must reevaluate Menzies’ competency before any execution can proceed. “We acknowledge that this uncertainty has caused the family of Maurine Hunsaker immense suffering, and it is not our desire to prolong that suffering. But we are bound by the rule of law,” the court stated in its order. This case highlights the complex intersection of justice, medical ethics, and constitutional protections that has become increasingly relevant in America’s aging death row population.

The circumstances surrounding Menzies’ case reveal the profound human complexity behind death penalty cases. Back in 1986, Maurine Hunsaker was abducted from her workplace, and despite calling her husband to say she’d been kidnapped but would be released, she was found dead two days later in Big Cottonwood Canyon, having been strangled with her throat slashed. For this horrific crime, Menzies was sentenced to death and, when given the option years ago, chose firing squad as his method of execution. Had his execution proceeded as scheduled, he would have become only the sixth U.S. prisoner executed by firing squad since 1977. Now, decades later, his attorneys argue that his physical and mental condition has deteriorated to the point where he uses a wheelchair, requires oxygen, and cannot comprehend why he faces execution—transforming what was once a straightforward capital punishment case into a profound ethical dilemma.

The legal battle over Menzies’ competency for execution brings to light significant precedents in American jurisprudence regarding the execution of individuals with serious mental impairments. Defense attorney Lindsey Layer noted that Menzies’ dementia has “significantly worsened” since his last competency evaluation more than a year ago, while the prosecution’s medical experts maintain he still possesses the mental capacity to understand his situation. This disagreement exemplifies the difficult judgments courts must make when determining if an execution would constitute cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment. The U.S. Supreme Court previously blocked the execution of Vernon Madison in Alabama in 2019 on similar grounds, ruling that a person cannot be executed if they cannot understand why they are being put to death. As the Court reasoned, if defendants cannot comprehend their punishment, executions fail to achieve the retribution that society seeks through capital punishment.

The impact of this case extends far beyond one man’s fate, touching the lives of many individuals connected to both the crime and the decades-long legal process. For Hunsaker’s family, who expressed being “very distraught and disappointed” by the court’s decision, this represents yet another painful chapter in their 38-year journey for closure. Their request for privacy speaks volumes about the lasting trauma that violent crime inflicts on victims’ families—trauma that is often prolonged by the extended legal battles characteristic of capital cases. Meanwhile, Menzies’ deteriorating condition raises uncomfortable questions about the purpose of executing someone who may no longer fully comprehend their crime or punishment. This case forces a societal reckoning with what justice truly means when decades separate the crime from the punishment, and when the person facing execution may be fundamentally changed by time and illness.

The method of execution itself—firing squad—adds another layer of complexity to this already multifaceted case. Utah’s last execution by firing squad occurred in 2010 with Ronnie Lee Gardner, while the state used lethal injection for its most recent execution just a year ago. South Carolina has more recently implemented firing squad executions, carrying out two earlier this year. The continued use of firing squads in the United States remains controversial, with proponents arguing it may be more humane than problematic lethal injection protocols, while critics view it as an archaic and barbaric practice. Menzies’ choice of this method decades ago now seems particularly poignant given his current condition—a man who once made a deliberate choice about how he would die may now be unable to comprehend that death is imminent, raising profound questions about autonomy, justice, and mercy.

This case ultimately forces us to confront uncomfortable questions about the purpose and limitations of capital punishment in contemporary society. As death row populations age nationwide, cases involving dementia and other age-related conditions will likely become more common, challenging our legal system to balance retribution with compassion, justice with humanity. The Utah Supreme Court’s decision recognizes that executing someone who cannot understand their punishment may serve neither justice nor society’s interests. As this case returns to a lower court for competency evaluation, it reminds us that our justice system must continuously reassess its practices against evolving standards of decency and constitutional protections. Whatever the final outcome for Ralph Leroy Menzies, his case illuminates the profound human and ethical dimensions of capital punishment—dimensions that extend far beyond legal technicalities to touch on fundamental questions about the meaning of justice in a civilized society.