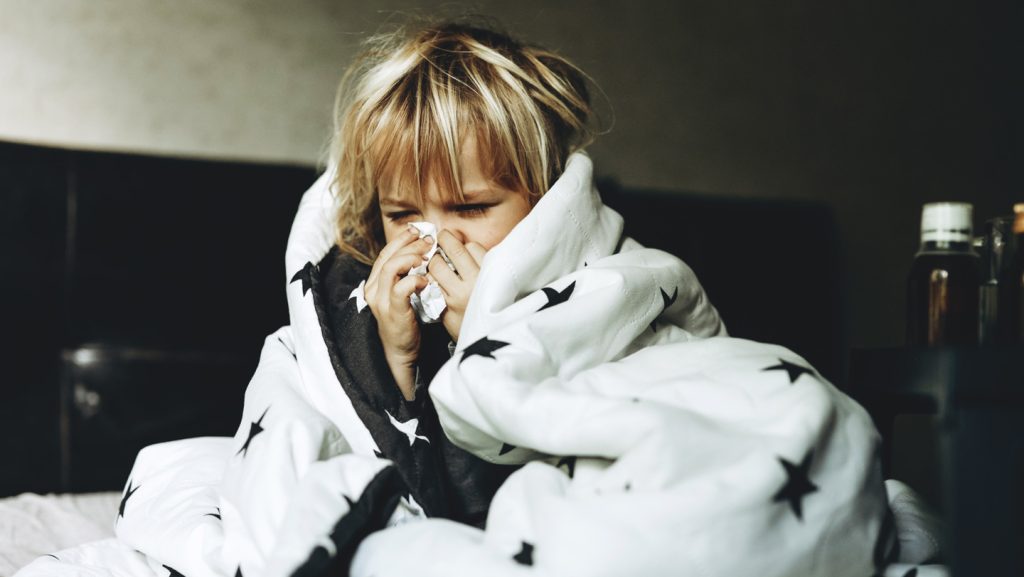

The Common Cold: An Unexpected Ally Against COVID-19

A recent scientific study has revealed an intriguing connection between the common cold and COVID-19, suggesting that our seasonal sniffles might actually provide some protection against the more serious coronavirus infection. Published in The Journal of Infectious Diseases on August 11, the research indicates that having a cold in the month before exposure to SARS-CoV-2 could cut your risk of infection by approximately half. This unexpected finding adds a new dimension to our understanding of how different respiratory viruses interact within the human body.

The study, which analyzed nasal swabs from over 1,000 participants, found that beyond just reducing infection rates, a recent cold appeared to make any subsequent COVID-19 infections significantly milder. Researchers discovered that people who had experienced a cold prior to contracting COVID-19 had almost ten times lower viral load – the amount of virus present in their body – compared to those who hadn’t had a cold. This reduced viral load is particularly important because it’s strongly associated with less severe illness and potentially reduced transmission to others.

What explains this protective effect? The researchers identified specific airway defense proteins that are activated when the body fights rhinovirus – the most common cause of the common cold. When these defense systems are already activated, they appear to create an environment that’s less hospitable for SARS-CoV-2 if it later enters the body. It’s as if having a cold puts the immune system on high alert, creating a readiness that benefits the body if coronavirus appears. This represents a fascinating example of how our immune responses to one pathogen can influence our body’s reaction to another, completely different virus.

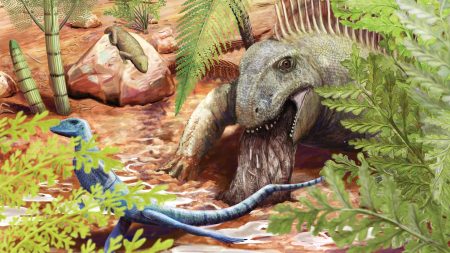

The findings emerged from analysis of data collected during the Human Epidemiology and Response to SARS-CoV-2 (HEROS) study, which ran from May 2020 to February 2021 and included nearly 1,400 U.S. households. The study had previously revealed that children were more likely than adults to experience asymptomatic coronavirus infections – an observation that puzzled scientists. Participants in the study regularly collected their own nasal swabs, allowing researchers to track infections over time and analyze the genetic material of different viruses present in the samples.

In exploring why children tend to experience milder COVID-19 symptoms, the researchers made another important discovery: the airway defense proteins triggered by rhinovirus infections were more highly activated in children than in adults. Additionally, children in the study were more likely to get colds in the first place. These two factors – more frequent colds and stronger protective responses to those colds – might help explain why kids generally fare better against COVID-19 than adults do. This provides new insights into the differences in immune responses across age groups and how common childhood infections might inadvertently prepare the body for other challenges.

While these findings don’t suggest that anyone should deliberately catch a cold to protect against COVID-19, they do highlight the complex interplay between different viral infections and our immune system. The research adds to our growing understanding of COVID-19 and potentially opens new avenues for developing antiviral strategies that mimic the protective effects observed. As scientists continue to unravel these relationships, we gain valuable knowledge that may ultimately help develop better approaches to preventing and treating respiratory infections of all kinds – showing once again how even seemingly simple conditions like the common cold can reveal surprising secrets about human health and immunity.