Let me tell you a story that feels as much about humanity’s darkest moments as it does about the enduring light of individuals who refuse to turn away. It’s the story of the Reverend François Ponchaud, a French Catholic priest who became an unexpected voice for truth in the face of unimaginable horrors. His life and work—filled with courage, compassion, and conviction—illuminated the catastrophic atrocities of Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge and ensured the world could not look away.

In the early 1970s, a thick fog of apathy and ignorance shrouded the West regarding the escalating nightmare in Cambodia. Political fatigue from the drawn-out Indochina wars had left many eager to turn their backs on Southeast Asia altogether. Yet, just as the world wanted to “move on,” Father François Ponchaud, an astute and unyielding man who had spent a decade immersed in Cambodian life, stood firm, unrelentingly demanding attention.

Born on February 8, 1939, in a small, idyllic village in the French Alps called Sallanches, François Ponchaud was no stranger to hard work. As one of 13 children, he grew up on a farm, tending to cows, pigs, chickens, and berry orchards, often wrestling with the realities of rural life. Maybe it was that foundation—a grounded life in the countryside—that granted him his deep sense of humanity. François was the only one of his siblings who felt a calling to priesthood. He left his family farm behind and ventured into seminary life, later serving as a French soldier in the Algerian War. Reflecting on this turbulent period, Ponchaud, who loathed the violence of war, admitted he participated out of fear of imprisonment. But as fate would have it, his decision to join the priesthood was destined for much larger purposes.

Following the war, his missionary work took him to Cambodia in 1965. Unlike missionaries eager to "convert," Ponchaud approached his role with a refreshing humility. “I came to Cambodia not to convert people,” he once explained, “but to help Cambodian people understand the value of their own religion.” Over the years, his deepening knowledge of Cambodian life and language enabled him to live deeply within its culture, allowing him to see its beauty and, later, its tragedy, with startling clarity.

All of that changed in April 1975, the year the Khmer Rouge overthrew Cambodia’s government. Almost immediately, the regime began implementing one of history’s most brutal social experiments, driven by a delusional desire for an agrarian utopia. It’s hard to grasp the scale of their ambition or their cruelty. Phnom Penh, the bustling capital city, was forcibly evacuated, leaving hospital patients wheeled out on stretchers or left abandoned on roadsides to die. The emptied cities became eerie monuments of what the Khmer Rouge envisioned: Year Zero.

This radical concept sought to erase all traces of Cambodia’s past—its history, culture, and foreign influences—resetting society to what the Khmer Rouge saw as a purified slate. Intellectuals, professionals, and even monks became prime targets, deemed dangerously tied to the "old ways." Systematic execution awaited anyone seen as a remnant of history. Torture houses and so-called killing fields multiplied across the country, where nearly two million people—almost a quarter of Cambodia’s population—suffered death by execution, starvation, or overwork.

Few figures in that era had both the moral conviction and the fortuitous positioning to chronicle these events like Father Ponchaud. Foreigners, including Ponchaud, were initially expelled from Cambodia, but rather than settle quietly, he spent the next years tirelessly documenting the unspeakable atrocities. Gathering hundreds of testimonies from refugees along the Thai border and from Cambodians who escaped to France, he pieced together a chilling mosaic of the Khmer Rouge’s barbarity. He also combined these firsthand accounts with the new regime’s own propaganda broadcasts—eerie windows into their dystopian mindset.

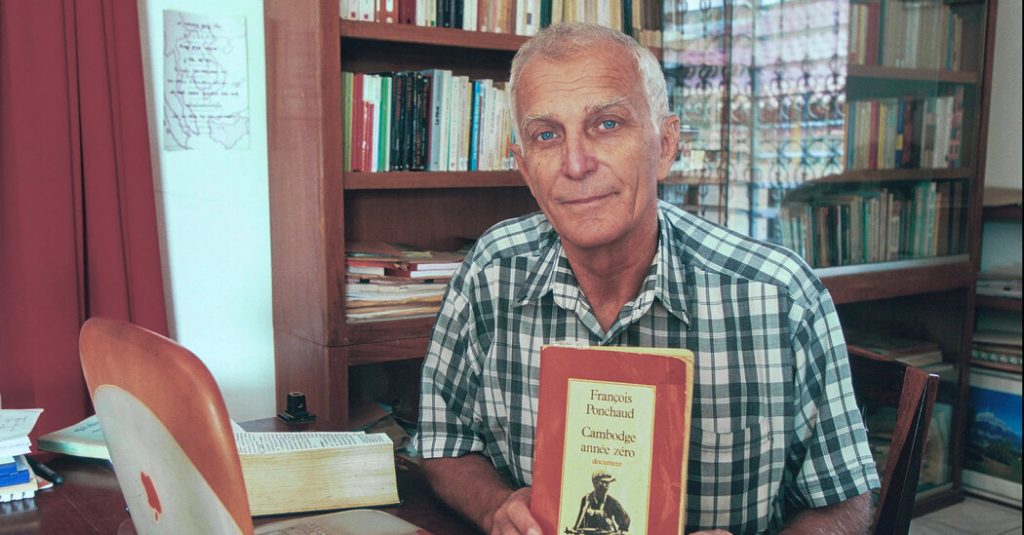

Ponchaud’s revelations weren’t welcome news. In 1977, he published Cambodia: Year Zero, a book that would come to define how the world remembered that gruesome period. Described as sober and detailed, the book delivered the horrors of the genocide in the raw, often using the refugees’ own voices to let their trauma speak for itself. The accounts were graphic but undeniable—stories of sick hospital patients left to die, children impaled before their families, and slaves toiling under inescapable conditions until their weary bodies gave way.

For some, like critics on the left who clung to romanticized notions of the Khmer Rouge as anti-colonial liberators, Ponchaud’s revelations were inconvenient truths. But for others, he was a clarion voice, persistent in exposing the truth at a time when many found it easier to ignore. “Ponchaud came as an annoyance to people who wanted everything to be lovely in Indochina,” said David P. Chandler, a leading historian of Cambodia. At a time when the West had grown weary of Southeast Asia’s turmoil, Ponchaud’s catalog of atrocities became a moral bellwether.

The priest’s connection to Cambodia didn’t end with his exposé. In 1993, long after the Khmer Rouge had been ousted by a Vietnamese invasion and years of subsequent civil war, Ponchaud returned to the country that had been his home and heartbreak. He founded a cultural center aimed at training priests and volunteers in Cambodia’s languages and traditions, reflecting his enduring love for its people and culture. He also set out to translate the Bible into Khmer, making Christian teachings accessible while continuing to honor the country’s Buddhist heritage.

Ponchaud’s interfaith sensitivity underscored his innovative approach to missionary work. He emphasized coexistence, reflecting that Buddhism and Christianity could complement rather than conflict with each other. “The teaching of Buddha, and meditation, allowed me to become a better Christian,” he said. “Buddha helped me to know who God is.” For Ponchaud, the sacred wasn’t about doctrines, but about unity and shared humanity.

In 2013, Ponchaud testified at a U.N.-sponsored trial against former Khmer Rouge leaders, recounting what he had directly witnessed: the forced evacuation of Phnom Penh, where crippled individuals crawled like worms in desperation. He testified in fluent Khmer, further underscoring his connection to the Cambodian people and culture. But he didn’t stop at recounting the regime’s atrocities; he also boldly highlighted the role of external powers, insisting even Henry Kissinger should be held accountable for the U.S. bombing campaigns that destabilized Cambodia and indirectly fueled the Khmer Rouge’s rise.

Ponchaud’s perspective wasn’t limited to a single chapter of Cambodia’s story, nor was it solely focused on exposing pain. “Our life is valuable even if we are poor,” he said in 2021. “We can walk together. This is the good news we proclaim in Cambodia today.”

François Ponchaud passed away on January 17, 2023, at 86 years old, succumbing to cancer at a retirement facility in France. His legacy, however, endures in the countless lives his work touched—both those he saved in bringing the Khmer Rouge to international attention and those inspired by his message of faith, compassion, and cultural respect. An alumnus of wars, atrocities, and healing efforts, his life reminds us that even during history’s darkest hours, the lights of truth and courage can still shine, often from those least expecting to be beacons. For Ponchaud, the Farmer’s Son-Turned-Missionary, his light was unwavering—one that pierced through Year Zero and left a path to remembrance and reconciliation that the world could follow.