The Neurological Underpinnings of PTSD Recovery: A Study of Resilience in the Aftermath of Trauma

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a complex and debilitating condition that can arise after exposure to a traumatic event. While much research has focused on the neurological mechanisms underlying the development and persistence of PTSD, a recent study published in Science Advances sheds light on the brain changes associated with recovery from this disorder. This groundbreaking research offers a more nuanced understanding of PTSD, emphasizing the brain’s remarkable capacity for plasticity and self-repair.

The study centered on 19 individuals who developed PTSD following the 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris but subsequently recovered over the ensuing years. The researchers compared their brain activity and memory performance with two other groups: those who experienced the attacks but did not develop PTSD and those who continued to suffer from chronic PTSD. Through a series of memory tasks conducted during functional MRI scans, the researchers were able to identify key differences in how the brains of these three groups processed and managed memories.

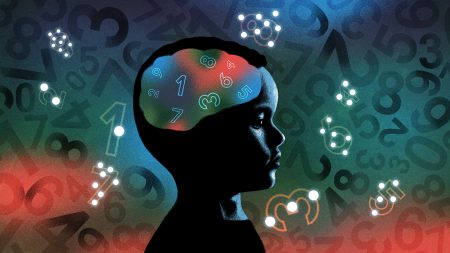

The memory tasks involved learning pairs of unrelated words and images, designed to mimic the associative learning that occurs in PTSD, where sensory stimuli can become linked to traumatic memories. Participants were instructed either to recall the associated image upon seeing the corresponding word or to suppress the image, effectively attempting to forget the association. The study revealed that individuals with PTSD initially exhibited distinct brain activity patterns during the memory suppression task compared to those without PTSD. However, over time, the brain activity of those who recovered from PTSD began to resemble that of the non-PTSD group. This suggests that the ability to suppress intrusive memories plays a crucial role in recovery, challenging the traditional view of PTSD primarily as a learning disorder and proposing it might alternatively be viewed as a "forgetting disorder."

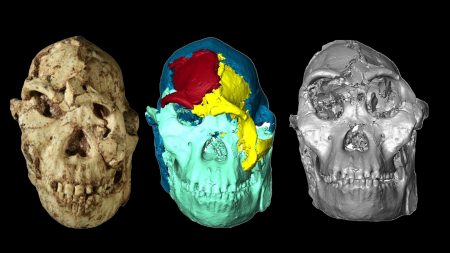

This "forgetting," however, does not equate to amnesia of the traumatic event. Recovered individuals retain their factual memory of the trauma but gain the ability to silence the intrusive, emotionally charged aspects of the memory, enabling them to regain control over their emotional responses. This shift in brain activity correlated with changes in the hippocampus, a brain region crucial for memory processing. While chronic PTSD patients showed a decrease in hippocampal volume over time, the hippocampi of recovering individuals stabilized, halting the atrophy observed in the chronic PTSD group.

The study’s findings underscore the dynamic nature of PTSD and highlight the brain’s potential for resilience. Recovery from PTSD is not simply a matter of extinguishing learned fear responses; it also involves regaining control over memory processes and preventing the debilitating intrusion of traumatic recollections. By focusing on the mechanisms that enable memory suppression and hippocampal recovery, future research may pave the way for developing more targeted and effective therapies for PTSD.

While the study provides compelling insights into the neurological correlates of PTSD recovery, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. The sample size is relatively small, and the study focuses on a specific type of trauma experienced by a specific population. Further research is needed to determine whether these findings generalize to other forms of trauma and across diverse populations. Additionally, PTSD is a heterogeneous disorder, encompassing a wide range of symptoms and symptom severity. It is possible that different neural mechanisms underlie recovery in different subgroups of individuals with PTSD.

The research nonetheless offers a hopeful message: recovery from PTSD is possible, and it is associated with tangible changes in brain structure and function. The brain possesses remarkable plasticity, allowing it to adapt and heal even after experiencing significant trauma. By unraveling the intricate neural circuitry involved in recovery, researchers are paving the way for developing innovative treatments that can bolster these natural resilience mechanisms and facilitate healing.

The findings present a paradigm shift in our understanding of PTSD. The focus on forgetting, or more precisely, active memory suppression, opens new avenues for therapeutic interventions. Instead of solely focusing on fear extinction, therapies could incorporate techniques that help individuals regain control over intrusive memories, allowing them to integrate the traumatic experience into their life narrative without being overwhelmed by its emotional intensity.

Furthermore, the observed changes in hippocampal volume suggest the possibility of neuroprotective strategies in PTSD treatment. By identifying factors that contribute to hippocampal atrophy and those that promote its recovery, it may be possible to develop interventions that prevent or reverse this neurobiological marker of PTSD, potentially enhancing the chances of sustained recovery.

The complexity of PTSD necessitates a multi-pronged approach to treatment, integrating both psychological and biological interventions. Future research should explore how the brain changes observed in recovering individuals can be facilitated through existing therapeutic modalities, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and exposure therapy. Additionally, the development of novel pharmacological and neuromodulatory treatments that target the specific neural circuits involved in memory suppression and hippocampal recovery holds tremendous promise for enhancing treatment outcomes.

The long-term implications of this research are significant. By moving beyond a purely deficit-focused model of PTSD, the study underscores the brain’s capacity for healing and adaptation. This perspective can empower both individuals struggling with PTSD and the clinicians who treat them, offering hope that recovery is achievable and that the brain possesses the inherent ability to overcome the devastating effects of trauma. As researchers continue to delve into the intricacies of PTSD recovery, the prospects for developing more effective and personalized treatments become increasingly promising. The brain is not static; it is a dynamic organ capable of remarkable resilience, and this inherent plasticity offers hope for a future where individuals can effectively heal from the wounds of trauma and reclaim their lives.