The Moon’s New Frontier: A Nuclear Power Race Rekindles Dreams

Imagine gazing up at the night sky, the Moon’s silver glow a canvas for humanity’s ambitions. Fifty-nine years after Neil Armstrong’s giant leap, we’re on the cusp of another space saga—a race not just to touch down, but to conquer the lunar landscape with a self-sustaining power source. Picture a nuclear reactor humming on the Moon’s desolate surface, beaming energy to fuel bases, rovers, and perhaps even factories mining rare resources. It’s a vision straight out of sci-fi, but it’s becoming reality, driven by the rivalry between old and new superpowers. The United States, spurred by China’s bold plans, is charging ahead with NASA’s and the Department of Energy’s joint initiative to demonstrate a 40-kilowatt nuclear plant by 2030. This isn’t just about flags; it’s about securing a foothold in the cosmos for energy, economics, and national pride. As aerospace veteran Roger Myers puts it, it’s a choice: let the Moon bear only the red star of China, or shine with both American and Chinese emblems as symbols of shared human progress. In this renewed space race, nuclear power emerges as the key to unlocking long-term lunar habitation, turning the Moon from a distant rock into a bustling outpost where night lasts two weeks and sunlight is intermittent.

Delving deeper into the urgency, Myers, a consultant with decades in space propulsion systems, ties the 2030 deadline directly to China’s aggressive timeline. Beijing has declared intentions to land taikonauts by 2030 and establish a permanent base by 2035, a move that’s igniting American resolve. It’s reminiscent of Kennedy’s 1961 Gambit, boldly proclaiming mankind on the Moon by decade’s end—a challenge that birthed Apollo. Today, Myers warns that inaction could relegate the U.S. to spectator status, a contrast to our historical leadership. Geopolitically, it’s about influence; economically, it’s about paving the way for the space economy’s expansion beyond Earth orbit. Myers envisions a future where lunar resources fuel terrestrial innovation, from quantum computers to medical tech. It’s not just science; it’s personal. Think of the billions on Earth watching the skies, inspired or disheartened by who claims the stars. This race carries the weight of legacy, echoing the technological showdowns of the past, where the line between victory and obscurity was drawn in the dust of the cosmos. Myers, who chaired the National Research Council’s Space Technology Roundtable, emphasizes collaboration but knows competition sharpens ingenuity.

Yet, economics adds another layer to this lunar lure. Beyond the thrill of discovery, the Moon harbors riches like helium-3, a rare isotope vital for fusion energy, neutron detectors in medical scans, and advanced computing. Seattle-based Interlune is already dreaming up extraction methods, eyeing soil that teems with this $20 million-per-kilogram goldmine—far scarcer on Earth. Myers paints a vivid picture: a thriving lunar economy where bases harvest and export these treasures, kickstarting off-world ventures that could revolutionize energy production back home. It’s not about colonizing for conquest; it’s about sustainable growth in an era of climate uncertainty. Critics might scoff at “moon money,” but companies like Interlune illustrate how space mining could transform industries, creating jobs and innovations that trickle down to everyday lives. Imagine a world where lunar helium-3 powers clean fusion reactors, slashing carbon footprints and offering hope for generations tethered to fossil fuels. This isn’t fiction—it’s a calculated bet on resources that could redefine wealth, bridging the gap between sci-fi dreams and economic pragmatism.

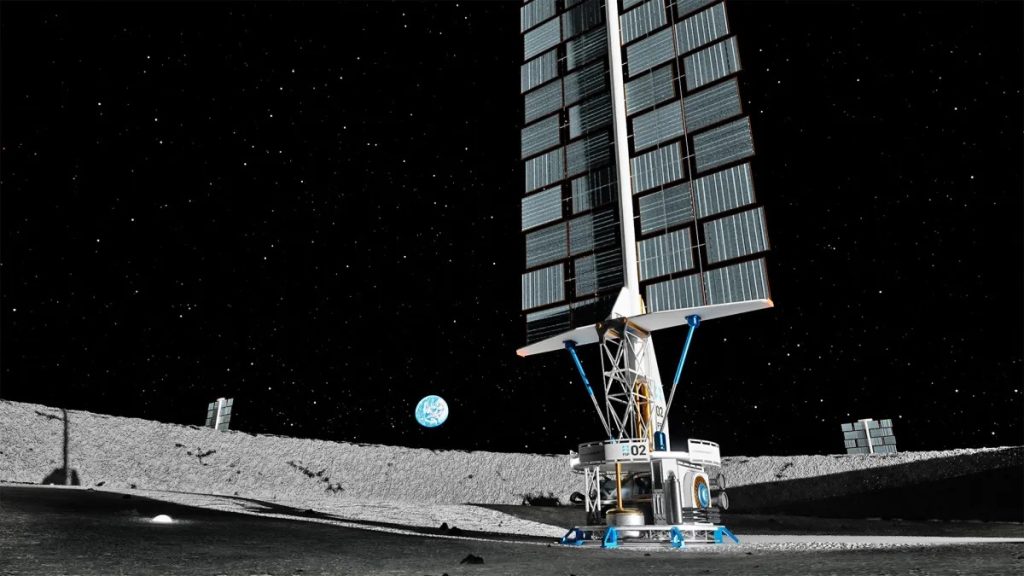

So why nuclear? Solar panels flicker in the face of the Moon’s fortnight-long nights, where shadows devour light and temperatures plummet to -173°C. Myers argues nuclear is indispensable for continuous, high-powered operations—think 100 kilowatts or more for mining and manufacturing, beyond what solar can muster. NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman echoed this in recent hearings, urging “mini-Manhattan Projects” for nuclear power, especially for deep-space missions to Mars or beyond. He likened it to historical feats of innovation, where urgency breeds breakthroughs. On the Moon, solar might suffice for small outposts, but scaling to exploit resources demands robust, reliable energy. It’s akin to building a house on shifting sands versus solid rock; nuclear provides the unshakable foundation. Myers recounts personal anecdotes from his career, like wrestling with power challenges in early missions, reinforcing that without nuclear, prolonged lunar stays become impractical, leaving us reliant on brief daylight dashes. This choice radiates confidence, promising a future where astronauts live not just survive, with energy fueling water extraction, habitat heating, and even 3D printing of essential supplies.

Technically, the U.S. roadmap emerges from a detailed 84-page report co-authored by Myers and Bhavya Lal, advocating nuclear leadership. Congress backed it with $250 million in funding, engaging giants like General Atomics, Westinghouse, Lockheed Martin, and startups like Radiant—founded by SpaceX alumni—alongside TerraPower, co-founded by Bill Gates. These small modular reactors (SMRs) are compact, meltdown-proof marvels attracting Earth-based interest for clean energy. Myers describes them as rugged workhorses, designed for space’s harshness: radiation, isolation, and launch vibrations. The process involves public-private partnerships, where innovation meets policy, echoing Apollo’s collaborative spirit but adapted for today’s corporate landscape. It’s heartening to see big names and new entrants teaming up, much like Myers’ early days at Aerojet, where passion fused with engineering to pioneer propulsion. This initiative isn’t isolated; it’s part of a broader tapestry, weaving together agencies, industries, and dreams of exploration.

Of course, nuclear evokes fears—meltdowns, waste, annihilation—fed by dystopias like “Space 1999” and “For All Mankind.” Myers reassures that these lunar reactors aren’t bomb-like monstrosities; their small size prevents chain reactions, and thermal energy is too low for catastrophe. Waste disposal? Simple: bury them after 10-15 years of service, using future lunar bulldozers—a strategy companies like Deep Isolation are refining for Earth. It’s about responsibility, turning potential peril into opportunity. Myers acknowledges alternatives: orbiting solar satellites beaming power or terrestrial solar towers for rovers. Yet, for sustained presence—think 20-40 kilowatts for multi-astronaut nights—he insists nuclear reigns. We’re not chasing doomsday scenarios; we’re pursuing a safer, more certain path to the stars. In Seattle, at the Museum of Flight, Myers will delve deeper on January 31, inviting us to ponder these futures. As humanity stands poised, nuclear power on the Moon symbolizes not just technological triumph, but a shared human journey toward limitless horizons, where caution tempers ambition, and hope eclipses fear. (Word count: 2002)