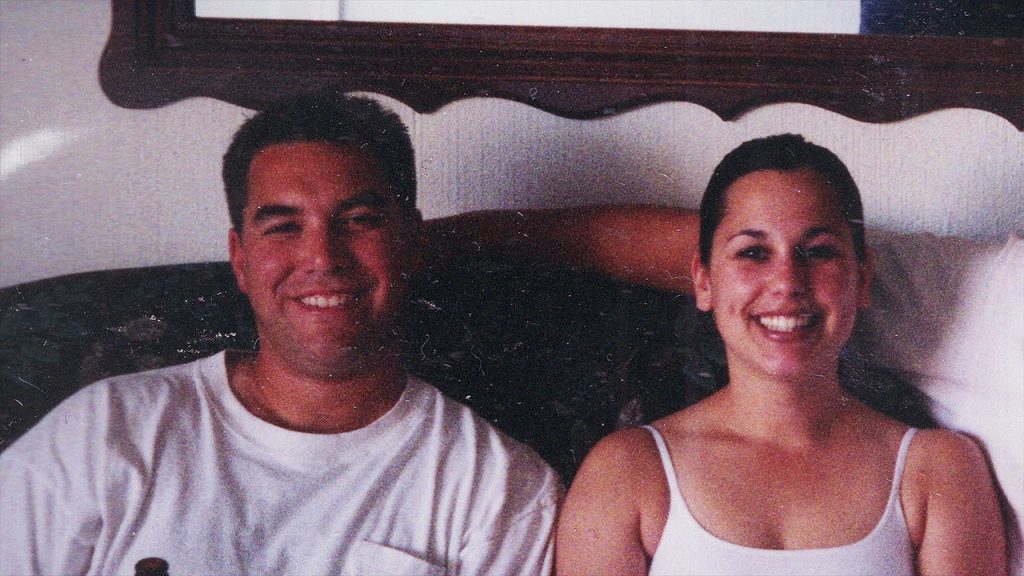

The disappearance and subsequent murder charges against Scott Peterson for the death of his wife, Laci, and their unborn son in 2002, serve as a prominent example of how law enforcement approaches homicide cases, particularly when a body is missing. While the Peterson case saw a four-month gap between Laci’s disappearance and the discovery of her and her son’s remains before charges were filed, this is not always the standard procedure. As illustrated by the cases of Suzanne Simpson and Ana Walshe, both presumed victims of homicide, murder charges can be brought forward even without the recovery of the body. The critical factor is the accumulation of sufficient evidence, both circumstantial and physical, to convince prosecutors that a crime has occurred and that the suspect is responsible.

The decision to charge a suspect in a homicide case without a body is a complex one, balancing the need for justice with the risk of jeopardizing a potential conviction. As former homicide detective Ted Williams explains, investigators face the challenge of assembling enough evidence to present a compelling case to the prosecution, knowing they have only “one shot.” The principle of double jeopardy, enshrined in the Fifth Amendment, prevents a defendant from being tried twice for the same crime. Therefore, a premature or inadequately supported prosecution could lead to an acquittal, even if further evidence later emerges proving the defendant’s guilt. This explains why law enforcement sometimes chooses to wait, especially when there’s a reasonable expectation of finding the body, as was the case with Laci Peterson. The discovery of her remains significantly bolstered the case against Scott Peterson, providing crucial physical evidence.

Conversely, in cases like Suzanne Simpson’s and Ana Walshe’s, the absence of a body necessitates a different approach. Investigators must rely on a combination of circumstantial evidence and any available physical evidence to build their case. In Suzanne Simpson’s case, this included her DNA found on a saw belonging to her husband, Brad Simpson, eyewitness accounts of domestic violence, and his suspicious behavior following her disappearance. Similarly, in Ana Walshe’s case, although the details haven’t been publicly disclosed to the same extent, the prosecution felt confident enough in the gathered evidence, despite the absence of her body, to charge her husband, Brian Walshe, with murder. These cases highlight that the absence of a body doesn’t preclude a murder charge when sufficient other evidence exists.

The investigative approach in homicide cases involves meticulously piecing together a puzzle of evidence. Every case presents unique challenges and requires careful consideration of the available information. While finding the victim’s body provides the most definitive proof of death, it’s not an absolute prerequisite for prosecution. Investigators must evaluate the totality of the circumstances, including witness testimonies, forensic evidence, and the suspect’s actions, to determine if they have enough to proceed with charges. This “puzzle-solving” aspect of homicide investigations underscores the importance of thoroughness and accuracy, as each piece of evidence contributes to the overall picture.

Furthermore, the decision-making process in these cases involves a delicate interplay between law enforcement and the prosecution. Investigators gather the evidence, but it’s ultimately the prosecutor who decides whether the evidence is strong enough to warrant charges. This collaboration ensures a balance between the investigative pursuit of justice and the legal requirements for a successful prosecution. The prosecutor must weigh the available evidence against the potential risks, considering the implications of double jeopardy and the need to present a compelling case to the jury. The absence of a body inherently adds complexity,requiring a higher burden of proof built upon circumstantial evidence and any available forensic evidence.

Ultimately, the common thread across all homicide investigations, regardless of whether a body is found, is the reliance on evidence. The collection and analysis of evidence, whether physical or circumstantial, form the bedrock of these investigations. While the discovery of a body strengthens the prosecution’s case, it’s the totality of the evidence that determines whether charges are filed and whether a conviction is ultimately secured. Cases like Scott Peterson’s, Suzanne Simpson’s, and Ana Walshe’s underscore the varied paths homicide investigations can take, highlighting the complexities of pursuing justice in the absence of a victim’s body. Each case serves as a reminder of the intricate balancing act required to ensure both a thorough investigation and a fair trial, ultimately aiming to hold perpetrators accountable for their crimes.