Brothers Freed After Unjust Sentences: A Tale of Legal Redemption in Mississippi

In a powerful story of justice delayed but ultimately delivered, Mississippi Governor Tate Reeves has granted clemency to Maurice Taylor, weeks after freeing his brother Marcus from an identical legal nightmare. Both men had been serving prison sentences that dramatically exceeded the maximum penalty allowed by law for their crime. Their case highlights troubling flaws in Mississippi’s criminal justice system and raises questions about how such legal errors could persist for years despite clear statutory limits on sentencing.

The brothers’ ordeal began in February 2015 when they both accepted plea bargains for conspiracy to sell hydrocodone acetaminophen, a Schedule III controlled substance commonly used to treat severe pain when other medications fail. Under Mississippi law, the maximum possible sentence for this offense was firmly established at five years. Yet astonishingly, Maurice received a 20-year sentence with five years suspended, while Marcus was handed 15 years behind bars. These sentences weren’t just harsh—they were explicitly illegal, exceeding the statutory maximum by three to four times. For nearly a decade, both brothers remained incarcerated despite the fundamental illegality of their punishment, trapped in a system that seemed unable or unwilling to correct its own mistake.

The path to freedom began with Marcus Taylor, whose case reached the Mississippi Court of Appeals earlier this year. In May, the court acknowledged his sentence was illegal but initially denied relief on procedural grounds, citing his missed deadline for post-conviction relief. Only after rehearing the case in November did the court reverse course and order his release. Maurice’s situation remained unchanged until his legal team contacted Governor Reeves’ office directly, presenting documentation that mirrored his brother’s case. In announcing Maurice’s clemency, Reeves spoke with unmistakable clarity: “Like his brother, Maurice Taylor received a sentence more than three times longer than allowed under Mississippi law. When justice is denied to even one Mississippian, it is denied to us all.” The governor ordered Maurice’s release within five days of his December announcement.

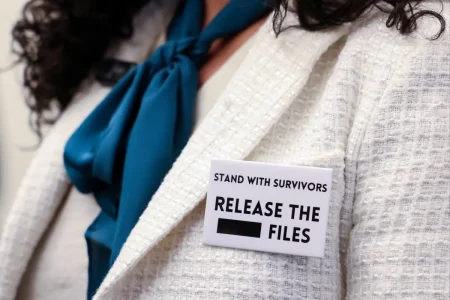

The Taylor brothers’ story represents a sobering look at how procedural barriers can prevent justice even when courts acknowledge that a fundamental legal error has occurred. For years, both men remained imprisoned on sentences that exceeded statutory maximums—a fact that should have triggered immediate review and correction within the legal system. Instead, it required sustained advocacy, media attention, and ultimately executive intervention to secure their freedom. The Mississippi Impact Coalition, which advocates for criminal justice reform, highlighted this troubling reality in their response to Maurice’s clemency: “This correction should have happened decades ago. It shouldn’t have taken relentless advocacy, public pressure, and the glaring contrast of one twin free while the other remained incarcerated to expose this injustice.”

What makes the Taylor brothers’ case particularly noteworthy is how it exposes multiple failures across Mississippi’s criminal justice system. The illegal sentences suggest potential failures at several levels: prosecutors who may have requested excessive punishments, defense attorneys who failed to object to illegal sentences, judges who imposed terms beyond statutory maximums, and an appeals process that initially prioritized procedural deadlines over substantive justice. While plea bargains represent agreements between defendants and prosecutors, they cannot legally exceed statutory maximums—a fundamental principle that was overlooked in these cases. The fact that these errors persisted for years raises serious questions about oversight and accountability within Mississippi’s criminal courts.

The Taylor clemencies mark a rare intervention by Governor Reeves, who has been notably conservative in using his clemency powers. These are the only two clemencies he has granted during his administration, suggesting the exceptional nature of the legal errors in these cases. As the brothers rebuild their lives after nearly a decade of wrongful incarceration, their story serves as both a cautionary tale and a call for reform. It demonstrates how easily individuals can be lost in a system that sometimes fails to apply its own rules correctly, and how difficult it can be to correct even the most obvious legal errors once the machinery of incarceration begins. While their freedom represents a victory for justice, the years lost to an illegal punishment can never be restored—making this both a story of redemption and a sobering reminder of work still needed to ensure Mississippi’s criminal justice system functions as intended for all citizens.