When Honeybees Invade: How Human Management Impacts Wild Bumblebees

In the picturesque Wicklow Mountains of Ireland, a spectacular natural phenomenon occurs each late summer when heather bursts into bloom, painting the landscape with vibrant purple hues. This floral spectacle has traditionally attracted beekeepers who transport their hives to these upland areas, allowing their honeybees to feast on the abundant nectar. However, a recent study published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences reveals that this seemingly harmless practice may have unexpected consequences for the local wild bumblebee populations. When commercial honeybees arrive in large numbers, they appear to create competition that results in smaller-sized local bumblebees and changes in their foraging behavior—potentially adding stress to these important wild pollinators that are already facing numerous threats in our changing world.

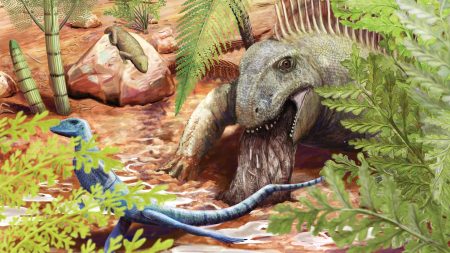

The study, led by researchers at University College Dublin, examined how the temporary influx of managed honeybees (Apis mellifera) affects native bumblebee species during the heather’s mass-blooming period. Unlike honeybees, which maintain year-round colonies, wild bumblebees operate on a more seasonal schedule with smaller colonies. During this critical late summer period, bumblebee workers are busy gathering resources—nectar for their own energy and pollen to feed developing larvae, some of which will grow into queens that will survive the winter while the rest of the colony perishes. The heather bloom represents a vital food source during this reproductive phase, making competition from suddenly-introduced honeybees potentially problematic for the wild bees’ lifecycle. As entomologist Dave Goulson of the University of Sussex colorfully describes it, “having lots of competitors arriving on the back of a lorry is not ideal” for these local pollinators.

To investigate the effects of this human-managed honeybee influx, ecologist Dara Stanley and her colleagues conducted fieldwork throughout the heathlands, carefully capturing and measuring specimens from six species of local bumblebees, including the white-tailed bumblebee (Bombus lucorum) and the small heath bumblebee (Bombus jonellus). They compared these measurements with honeybees from nearby managed hives and made some intriguing discoveries. While the number of bumblebees in honeybee-dense areas remained consistent with other locations, their physical size showed a noticeable difference—bumblebees in areas heavily populated by honeybees were measurably smaller than their counterparts elsewhere. This size discrepancy could reflect two possible scenarios: either larger bumblebees were deliberately avoiding crowded feeding areas in favor of better opportunities elsewhere, or bumblebee colonies were struggling to gather sufficient resources, forcing them to produce smaller workers or send more foragers out to compensate for limited food access.

Further behavioral observations revealed another significant pattern: the smaller bumblebees found in honeybee-crowded areas were more likely to be collecting pollen rather than nectar. This shift in foraging preference suggests a strategic adaptation under pressure. As Stanley explains, pollen serves as nutrition for developing bee larvae, so “when a colony is under stress, it might prioritize reproduction or pollen collection for larva.” This behavioral change indicates that bumblebee colonies may be adjusting their resource-gathering priorities when faced with competition, focusing more on ensuring the next generation’s survival than on gathering nectar for immediate energy needs. While this adaptation may help the bumblebees cope with competition in the short term, it raises questions about the long-term sustainability of such adjustments, particularly if they come at the cost of worker bee nutrition or colony health.

Although these observed changes in bumblebee size and behavior might seem subtle, they could have meaningful implications for conservation practices. The research provides valuable insights that could help guide more ecologically sensitive beekeeping practices. Goulson suggests that while moving honeybee hives to flowering areas might be acceptable in agricultural settings, they should probably be kept away from natural heathland reserves that serve as critical habitat for wild pollinators. “We do know that wild pollinators have been in decline for quite some time,” he notes, emphasizing that “anything that contributes to their woes is something we should pay attention to.” This perspective highlights the broader context of global pollinator decline and the importance of considering how human activities, even those as seemingly benign as beekeeping, might inadvertently contribute to the challenges facing wild bee populations.

The findings from this Irish heathland study exemplify the complex ecological interactions that can occur when human management practices intersect with natural systems. As we continue to navigate the balance between agricultural needs and ecological preservation, such research offers valuable guidance for more sustainable approaches. By understanding how managed honeybees interact with wild pollinators, we can develop more thoughtful practices that support both agricultural productivity and biodiversity conservation. For the wild bumblebees of Ireland’s purple heathlands, the solution may be as simple as giving them a little more space to forage without having to compete with busloads of honeybee tourists descending on their floral feast.